Home » Posts tagged 'Neolithic' (Page 2)

Tag Archives: Neolithic

Wiltshire house rivalled Stonehenge as a hub for ancient Britons

Neolithic building on vast site at Marden Henge is welcoming public visitors again after thousands of years buried beneath farmland.

Pieces of flint tools dropped more than 4,300 years ago on the floor of a house as old as Stonehenge have been laid bare on the edge of Marden Henge, a giant ditch and bank enclosure so buried in rich Wiltshire farmland that it has almost vanished from view.

“We’ve over-fetishised Stonehenge for far too long, because those giant trilithons are just so damn impressive,” said Dr Jim Leary, director of this summer’s excavation with the Reading University archaeology summer school, in the lush Vale of Pewsey. “It could well be that this was really where it was at in the Neolithic.”

The rectangular building will welcome visitors next weekend for an open day which is part of the national festival of archaeology. The house, believed to be one of the best preserved from the period ever found in the UK, and made to look smarter with tonnes of white chalk brought from miles away and stamped into a kind of plaster, is as neatly levelled and regular as the nearby postwar bungalows built on top of part of the henge bank.

The house and other parts of the huge site have already produced finds including beautifully worked flint arrowheads and blades, decorated pottery including some pieces with the residue of the last meals cooked in them, shale and copper bracelets and a beautiful little Roman brooch – and the tiny jawbone of a vole. Analysis of the mass of seeds and charred grains recovered will reveal what the people were growing and eating.

Pig bones – probably the remains of at least 13 animals, food for hundreds of people – and scorch marks from a charcoal firepit suggest the house was never a permanent residence but connected with great gatherings for feasts. When it was abandoned the entire site, pig bones and all, was cleaned and neatly covered with earth, so it would never be used again.

The structure originally stood on a terrace overlooking a mound, within a small earth-banked circle, in turn part of the enormous Marden Henge.

Leary, joined by archaeology students, professionals and amateurs from all over the world, who will continue working on the site for years to come, is peeling back the layers of a monument that was once one of the biggest and most impressive in Britain. Ramparts three metres high enclosed a vast space of 15 hectares, far larger than the Avebury or Stonehenge circles, and too large for any imaginable practical use.

Leary believes the purpose must have been status, showing off wealth and power in the ability to mobilise a massive workforce. “Avebury had the huge ditches, Stonehenge upped the ante with the massive trilothons, Marden had this enormous enclosure.”

The site is so vast that it takes Leary and fellow director Amanda Clarke 40 minutes to walk from the team working on the house to the diggers who have uncovered a previously unrecorded Roman complex including the foundations of an impressive barn.

Like the Durrington Walls henge a few miles downstream, and Stonehenge itself, Marden was linked to the river Avon by a navigable flow, now a sedge- and nettle-choked stream, which forms one side of the henge.

“Avebury in one direction and Stonehenge in the other have been excavated and studied for centuries because the preservation of the monuments on chalk is so much better. Not nearly enough attention has been paid to the archaeology of the fertile valleys because the land is so good the monuments have often been ploughed out above ground – but it is a key part of understanding the story.”

Marden’s banks, cut through by later roads or lying under modern farm buildings, grazing cows and ripening crops in many places, once stood three metres tall, towering over an equally deep ditch. The outer ring enclosed a complex of smaller monuments, including the Hatfield Barrow, which was once 15 metres tall, and now survives only as a 15cm ripple in the field. It was excavated in 1807 and, after a collapse caused by the shaft, later completely levelled by the farmer.

The site welcomes visitors every day, but the open day will have finds on display, tours and activities. It will be among more than 1,000 events across the country over the last fortnight of July, including lectures, site tours and visits to archaeology stores and structures normally closed to the public.

- The Reading University archaeology summer field school open day takes place at Marden Henge, Wiltshire, on 18 July. The Council for British Archaeology festival of archaeology runs nationwide from 11-26 July.

Stonehenge and Avebury Guided Tours

http://www.StonehengeTravel.co.uk

Avebury Stone Circle: Mystery and secrets all set in stone.

MARK THORNTON (Western Australian) finds ancient tales and spirits permeate at prehistoric Avebury.

What’s the connection between a prehistoric English monument older than Stonehenge, marmalade and a Victorian MP?

The English prehistoric site is the Neolithic stone circle at Avebury in Wiltshire. The MP is Sir John Lubbock, who bought it in 1871, and the marmalade connection comes from Alexander Keiller, who made his fortune from the confection and used it to buy the site 20 years after Sir John’s death.

Avebury, encompassing 11.5 hectares, is the largest prehistoric stone circle in the world. Construction was intermittent and spanned hundreds of years but was completed around 2600 BC. It’s 14 times larger and 500 years older than Stonehenge, 30kms to the south.

As with Stonehenge, many people have theories as to why it’s there. One is that it was the focal point of large-scale religious ceremonies and rituals during the Neolithic and Bronze ages. Another is that the shape and alignment of the stones, which have almost geometric precision, suggest it was an astronomical observatory.

Antiquarian Dr William Stukeley first visited the site in the 1720s and after 30 years research, claimed the original ground plan of Avebury represented the body of a snake passing through a circle to form a traditional symbol of alchemy. Other researchers have since said it was a centre of science, learning, pilgrimage, a cultural meeting place for regional tribes, and even a hub for extra-terrestrial activity—though this suggestion was made in the 1960s when hippies with vivid imaginations, and often heightened sensibilities, discovered the site. Sadly whoever built Avebury left no written or pictorial clues.

The site consists of a circular bank of chalk 425 metres in diameter and six metres high, enclosing a ditch that was nine metres deep when dug but after 4600 years of weathering, still has a depth of more than six metres. Archaeologists estimate the ditch would have taken nearly 300 people 25 years to complete and required 200,000 tons of rock to be chipped and scraped away with crude stone tools and antler picks. This suggests a sizeable, stable and well-organised local population lived at the site with a successful agrarian economy able to support the build. However, they had disappeared long before the Saxons built a settlement there 1500 years ago. The word Avebury probably comes from Ava, the Saxon leader at the time.

Inside the ditch there is a circle of 27 sandstone pillars, each weighing up to 50 tons. There used to be three times that many, but over the past 1000 years local villagers used the site as a quarry for building materials. Inside the circle of sandstone pillars are the remains of two smaller stone circles, each originally consisting of about 30 uprights and each about 105 metres in diameter. At the centre of the southern inner circle a tall obelisk once stood surrounded by smaller boulders.

It’s a big and impressive site, and due to the presence of Avebury village, built inside the ring of stones with its church and edged by some ancient large trees, it’s softer and less foreboding than Stonehenge. Nonetheless, it has a strong sense of mystery. Four huge beech trees stand out, each with a spectacular tangle of roots spread over the surface of the chalk bank. Locals call them the Tolkien Trees, claiming J R R Tolkien was inspired by them to create the Ents for Lord of the Rings. Meandering among the stones in the late afternoon under a lowering sky it’s easy to give your imagination free rein.

Avebury is more accessible than Stonehenge, which is now fenced off and requires you to buy your $30 admission tickets— that only give you two hours on site— in advance. Avebury has no admission fee, fences or closing times and you can walk among the ancient stones and mounds as long as you like, soaking in the mystery. Some people even camp among the stones. It’s this ambience that attracted Sir John Lubbock and later marmalade baron and amateur archaeologist Alexander Keiller.

Sir John, a close friend of Charles Darwin, was a visionary whose main political agendas in Parliament included promoting the study of science in primary and secondary schools and protecting ancient monuments. He invented the terms ‘palaeolithic’ and ‘neolithic’ to denote the old and new stone ages. He bought Avebury in 1871 when the locals seemed bent on destroying it by using the ancient stones as building material. Some cottages still have large pieces of the standing stones as massive cornerstones.

Sir John was responsible for the Ancient Monuments Act in 1882, the first piece of legislation that protected archaeological sites, paving the way for English Heritage.

Pious locals had begun destroying the site more than 1000 years earlier with the encouragement of the Christian church, which controversially urged the destruction of pagan symbols, yet was not averse to encouraging the villagers to build a church in the village from those same ‘pagan’ stones. During his tenure and oversight of repairs Sir John discouraged any more building within the site, describing the village and its church to be “like some beautiful parasite (that) has grown up at the expense and in the midst of the ancient temple”.

When he was raised to a peerage in 1900 Sir John chose Avebury for his title, becoming Lord Avebury thereafter.

Keiller bought the site, including the entire village with its then population of about 500, in 1934 with the intention of completing Lord Avebury’s work in restoring it. He knocked down cottages and farm buildings to remove human habitation from within the stone circle and re-erected fallen stones and set concrete markers in places where stones originally stood. In doing so he both upset and impressed villagers, who soon came to accept him as a well-meaning eccentric who brought work to what was a poor community. He spent the equivalent of $4 million in today’s money on the restoration, which includes a magnificent museum. He sold the site to the National Trust in 1943 and his widow donated the museum to the nation in 1966.

The museum is worth a visit on its own. Particularly fascinating is its collection of ancient jewellery made from rare metals and bronze, many featuring semi-precious stones. Although made thousands of years ago, the jewellery has in its perfect simplicity a timeless style and beauty.

Avebury is well worth a visit, not just for itself, but for a number of other prehistoric sites nearby, including Silbury Hill and the West Kennet Long Barrow (a burial mound), both of which are several hundred years older than Avebury. Together they lie at the centre of a collection of Neolithic and early Bronze Age monuments and all are part of a World Heritage Site in a co-listing with Stonehenge.

Stonehenge and Avebury Guided Tours

The Stonehenge Travel Company

Salisbury

Stonehenge: no more going round in circles

After decades of delay, Stonehenge’s new visitor centre finally opens to tourists today. So has it been worth the wait? Simon Calder takes a tour round this gateway to the Neolithic past

The ancients might be amused that the problem of “What shall we do with Stonehenge?” has lasted about as long as Neolithic man took to construct England’s emblem in the first place. Conflict between the preservation of this astonishing temple to the sun and the demands of tourists, motorists and the military is as old as the Wiltshire downs. But from this morning, the struggle may be over.

“Standing here now it is hard to describe the feeling of relief, excitement and elation that I feel,” says Simon Thurley, chief executive of English Heritage.

“Here” is the new visitor centre, gateway to the nation’s most significant ancient site. Late Neolithic man bequeathed us the only lintelled prehistoric stone circle in the world – and the lintels are responsible for the allure. While Scotland has more impressive stone circles, at Callanish on Lewis and Brodgar on Orkney, the structure here resembles a series of doors that invites the onlooker to gaze in on the past. But how to make sense of it all? Interpretation for the million-plus annual visitors to Stonehenge has, up to now, been dismal.

Among the many planning outrages that were being perpetrated in the Sixties, Stonehenge escaped relatively lightly. While Euston station was being demolished and Plymouth city centre was being constructed, the 4,500-year-old circle of English “sarsen” stones and Welsh bluestone was given a 1968 upgrade of its own. The quasi-military bunker has served, for 45 years, as a visitor centre in the loosest sense of the term. Hemmed in by car and coach parks, it felt like a suburban muddle rather than a gateway to the past – more Penge than henge. Its doors closed yesterday, thank goodness, and from this morning the site will be treated with more dignity.

The elegant new visitor centre is a post-modern solution to a prehistoric problem. It is the heart of a much-delayed £27m package of improvements designed to rescue the temple complex from centuries of abuse. The director pronounces herself “hugely pleased” with the results. “It’s such a beautiful building that sits so well in the landscape,” says Loraine Knowles.

Were I called upon to sum up the design in three words, they would be “Nordic airport terminal”. Which suggests either that the needle-thin columns soaring to perforated eaves like a deconstructed Rubik’s Cube are a touch adventurous for Wiltshire, or that I have spent too long hanging around Tromso and Turku. The materials, though, are strictly local.

The platform upon which the new tourist temple sits has travelled far less distance than the stones – it is a limestone raft quarried near Salisbury. And the wooden benches in the light, spacious café look as though they may have been purloined from the branch of Wagamama in the same city. But high-spec furnishings are the least you’d expect after paying £14.90 to get in – up from £8 since yesterday.

After experiencing the breathtaking new exhibits on the south side of the terminal – sorry, visitor centre – however, you will probably judge the 86 per cent admission hike to be fair. Expertise, electronics and hard cash have combined to explain the Stonehenge saga eloquently.

Over a few centuries, archaeologists’ understanding of the “what”, “when”, “how” and “why” of Stonehenge has steadily refined – but until the 21st century the notion of “who” has been as opaque as the morning mist.

“In the past 10 years, our understanding of Stonehenge has been revolutionised,” says Simon Thurley.

Today, the visitor gets to stand amid a virtual stone circle at the start of the exhibition area, as projectors play a continuous cycle through the seasons of Stonehenge, catching the rising sun on the summer solstice and the setting sun of midwinter. Then the scale of the sacred engineering is explained: 35-ton lumps of ultra-hard sandstone – known as sarsen – were dragged south from the Marlborough Downs, while smaller slabs of bluestone were fetched from the Preseli Hills in west Wales, 150 miles away.

The building of a temple, initially for cremation ceremonies, was carried out with only the most rudimentary of tools; antlers were a favourite for earthworks.

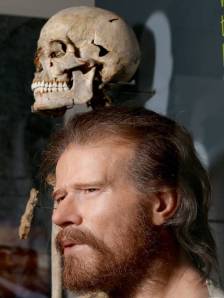

But what did the builders of Stonehenge look like? English Heritage has commissioned a best guess. A Swedish expert in forensic reconstruction has created a handsome, bearded head from studying a skull found on the site.

The final element of the visitor centre is an area for temporary exhibitions – the first of which is an enchanting account of how Stonehenge has been interpreted over the centuries. Medieval man believed it to be a marvel brought by Merlin from Ireland. The circle was also attributed over the centuries to Romans and Druids, before finally being marked down as the work of good-natured ancient Britons.

The visitor centre is opening just in time for this Saturday’s winter solstice – and not a moment too soon for anyone, such as Dr Thurley, who agrees that the presentation of Stonehenge has been “a national disgrace”. That was the term used by the Public Account Committee 20 years ago. Since then, successive governments have come up with a range of proposals that typically involve doing to the A303 what Neolithic man did to the deceased: bury it in the downland.

The main road between London and the South-West still rumbles above ground, 200 yards south of the stone circle, but at least the A344 has closed. Previously, the short-cut from Amesbury to Warminster tore along the northern flank, but now the two-mile highway is no more. The busy junction with the A303 has been grassed over, a mere 29 years after Lord Montagu, the first chairman of English Heritage, called for its closure.

The former roadway has been put to use to provide access to the stones. Tourists are towed to the periphery aboard the sort of sightseeing shuttle normally found at the seaside.

If you book an early-morning or after-hours tour with English Heritage, you can enjoy a gratifying close-up of ancient Britain. Daytime visitors are kept at much more than arm’s length. But that distant encounter is at last properly poignant. “It allows us to reunite the stones with the grass downland,” says Dr Thurley.

The low roar from the A303 may still be too close for comfort, but no longer is the ancient stone circle trapped in the headlights of progress.

Travel essentials

Getting there

By road, the new visitor centre is a mile north of the A303 on the A360; the postcode is SP3 4DX.

The nearest station is Salisbury, on the London-Exeter and Bristol-Southampton lines. Buses run to Stonehenge.

Getting in

The site opens 9.30am-5pm daily, though over Christmas and the New Year there are some shorter hours and closures; see bit.ly/GoStone. That is also the place to make advance bookings, which English Heritage says will be mandatory from 1 February. The advance adult admission is £13.90, or £14.90 for walk-up arrivals.

Aricle by Simon Calder : http://www.independent.co.uk/travel/uk/stonehenge-no-more-going-round-in-circles-9011327.html

Join us on a private access tour of Stonehenge from Salisbury

The Stonehenge Travel Company, Salisbury, Wiltshre

The Stonehenge Experts

Before Stonehenge – did this man lord it over Wiltshire’s sacred landscape?

Archaeologists have just completed the most detailed study ever carried out of the life story of a prehistoric Briton

What they have discovered sheds remarkable new light on the people who, some 5500 years ago, were building the great ritual monuments of what would become the sacred landscape of Stonehenge.

A leading forensic specialist has also used that prehistoric Briton’s skull to produce the most life-like, and

How 21st-century science is recreating the life story of a neolithic leader – what he looked like, where he grew up and what he ate

arguably the most accurate, reconstruction of a specific individual’s face from British prehistory.

The new research gives a rare glimpse into upper class life back in the Neolithic.

Five and a half millennia ago, he was almost certainly a very prominent and powerful individual – and he is about to be thrust into the limelight once again. For his is the prehistoric face that will welcome literally millions of visitors from around the world to English Heritage’s new Stonehenge visitor centre after it opens tomorrow, Wednesday. The organisation estimates that around 1.2 million tourists from dozens of countries will ‘meet’ him as they explore the new visitor centre over the next 12 months.

The new scientific research has revealed, to an unprecedented degree, who this ‘face of prehistory’ really was.

He was born around 5500 years ago, well to the west or north-west of the Stonehenge area, probably in Wales (but conceivably in Devon or Brittany)

Aged two, he was taken east, presumably by his parents, to an area of chalk geology – probably Wiltshire (around the area that would, 500 years later, become the site of early Stonehenge). However, aged 9, he then moved back to the west (potentially to the area where he had been born) – and then, aged 11, he moved back east once more (again, potentially to the Stonehenge area).

Aged 12, 14 and 15, he travelled back and forth between east and west for short durations and at increased frequency. Scientists, analysing successive layers of the enamel in his teeth, have been able to work all this out by analysing the isotopic values of the chemical elements strontium (which changed according to underlying geology) and oxygen which reflected the sources of his drinking water.

He grew into a taller than average man, reaching an adult height of 172 centimetres. In Neolithic Britain, the average height for adult males was 165 centimetres, while in Britain today it is 176. He probably weighed around 76 kilos (12 stone) and had fairly slender build. Throughout his life, he seems to have consumed a much less coarse diet than was normal at the time . His teeth show much lighter wear than many other examples from the Neolithic. He also had a much higher percentage of meat and dairy produce in his diet than would probably have been normal at the time.

By analysing nitrogen isotope levels in his teeth, a scientific team at the University of Southampton, led by archaeologist Dr Alistair Pike, have worked out that he obtained 80-90% of his protein from animals – probably mainly cattle, sheep and deer.

A detailed osteological examination of his skeleton, carried out by English Heritage scientist, Dr Simon Mays, has revealed that he probably led a relatively peaceful life. The only visible injuries showed that he had damaged a knee ligament and torn a back thigh muscle – both injuries, potentially sustained at the same time, that would have put him out of action for no more than a few weeks.

There is also no evidence of severe illness – and an examination of hypoplasia (tooth enamel deformation) levels suggest that at least his childhood was free of nutritional stress or severe disease. Hypoplasia provides a record of stress through a person’s childhood and early teenage years.

But he seems to have died relatively young, probably in his late 20s or 30s. At present it is not known what caused his death.

However, he was probably given an impressive funeral – and certainly buried in a ritually very important location.

Initially his body was almost certainly covered by a turf mound but some years or decades later, this mound was massively enlarged to form a very substantial mausoleum – one of the grandest known from Neolithic Britain. He was the only individual buried there during his era – although a thousand or more years later, several more people were interred in less prominent locations within the monument.

This great mausoleum – 83 metres long and several metres high – was treated with substantial respect throughout most of prehistory – and can still be seen today some one and half miles west of Stonehenge. Fifteen hundred years after his death, his tomb became the key monument in a new cemetery for the Stonehenge elites of the early Bronze Age.

All the new evidence combines to suggest that he was a very important individual – a prominent member of the early Neolithic elite.

The research into his life has yielded a number of fascinating new revelations about that period of British prehistory.

First of all, it hints at the degree to which society was stratified by this time in prehistory. Far from being an egalitarian society, as many have tended to think, the evidence points in the opposite direction. Most early Neolithic people were not given such grand mausolea . The type of monument which was constructed over his grave (known to archaeologists as a long barrow) was primarily a place of ritual, not just a place associated with burial. By having one erected over him, he was being given a very special honour.

Of the 350 such long barrows known in Britain, it is estimated that 50% had no burials in them at all, that a further 25% had just one person buried in them – and that most of the remaining quarter had between five and 15 buried in each of them.

Secondly, it shows, arguably for the first time, that high social status in the early Neolithic was already a matter of heredity. The isotopic tests on the man’s teeth show quite clearly that his privileged high meat diet was already a key feature in his life during childhood.

Thirdly, the scientific investigation suggests that at least the elite of the period was associated with a very wide geographical area. In other words, they were not simply a local elite but, at the very least, a regional one. The fact that he seems to have moved back and forth between the west of Britain (probably Wales) and the southern chalklands (probably the Stonehenge area) every few years, at least during his childhood and teenage years, suggests that his family had important roles in both areas.

Given the ritual significance of the Stonehenge area, even at this early stage, it is possible that he and his father and other ancestors before him had been hereditary tribal or even conceivably pan-tribal priests or shamans in a possibly semi-nomadic society. It is also likely that such people also played roles in the secular governance of emerging political entities at the time.

Most tantalizing of all, is the newly revealed likely link between Wales and the pre-Stonehenge ritual landscape. When the first phase of Stonehenge itself was finally built in around 3000 BC, the stones that were probably erected there were not, at that stage, the great sarsens which dominate the site today, but were probably the much smaller so-called ‘bluestones’ (some of which are still there).

Significantly, it is known from geological analysis that those bluestones originally came from south-west Wales – and were therefore almost certainly brought from there to Stonehenge by Neolithic Britons.

Indeed, as late as the 12th century AD, the Anglo-Norman chronicler, Geoffrey of Monmouth, wrote down an ancient legend also suggesting that the stones had come from the west (albeit, in his account, from Ireland, rather than Wales). Archaeologists will now be investigating whether the Stonehenge landscape’s link with Wales was in reality even older than that first phase of the monument.

In that sense it is spookily relevant that the mid-fourth millennium BC man chosen by English Heritage to be the ‘face of the Neolithic’ may actually have been a key part of the original cultural process which ultimately, five centuries later, led to early Stonehenge being erected.

The new visitor centre – built with steel, wood and glass in ultra-modern style – tells the story of Stonehenge and its prehistoric ritual landscape and illustrates it with 300 mainly stone and ceramic artefacts from antiquarian and archaeological excavations carried out around the great stone monument over the past two centuries

David Keys: Archaeology Correspondent

Full article in the Independent: http://www.independent.co.uk/news/science/archaeology/before-stonehenge–did-this-man-lord-it-over-wiltshires-sacred-landscape-9008683.html

Stonehenge Travel Company

Stonehenge Guided Tours from Salisbury